Strengthening the human capacity of creativity is at the basis of much of UNESCO’s work, which recognizes creativity as a multifaceted human resource that can inspire positive, transformative change for present and future generations. Creativity, embracing cultural expressions and the transformative power of innovation, is an integral part of human ingenuity and contributes to finding imaginative and appropriate responses to development challenges. Tapping into creative assets is a viable way of making globalization more human, now and in the future. Creativity is essential to promoting peace and sustainable development. For these reasons, UNESCO included ‘Fostering creativity and the diversity of cultural expressions’ in the list of strategic objectives of its current Medium-Term Strategy and attributed a central place to the safeguarding of intangible cultural in the program and action under this objective.1

Indonesian batik design on men’s ceremonial head cloth, circa 1880

Creativity is indeed a key concept of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, which conceives of intangible cultural heritage as the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, and skills that are continuously created and recreated when transmitted from generation to generation. The Convention recognizes that intangible cultural heritage ‘is constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment, their interaction with nature, and their history.’ Creativity is therefore a defining characteristic of intangible cultural heritage that does not occur in a vacuum. It is always living and changing as a result of the transmission and safeguarding process. While intangible cultural heritage is derived from the past, as living heritage it necessarily belongs to the present and the future. The Preamble of the Convention echoes the intrinsic connection between intangible cultural heritage and creativity, explaining that communities and groups involved in the production, recreation, and transmission of intangible cultural heritage are ‘helping to enrich cultural diversity and human creativity.’

Examples exist in abundance. Many oral traditions, for example, thrive on interpretation and improvisation, such as the practice of Al-Zajal, which is a form of Lebanese folk poetry in which the performers, both men and women, express themselves either individually or collectively on a variety of themes including life, love, nostalgia, death, politics, and daily events. They constantly reinvent the content of their poetry to create meaning that is relevant to the changing social and cultural concerns of their audiences.2

In the broad domain of social practices and rituals, we find many lifecycle rituals related to birth, adolescence, marriage, and death that are continuously recreated in relation to changing social norms and circumstances, including gender-related norms. In Mauritius, Geet-Gawai is traditionally performed as a pre-wedding ceremony by Bhojpuri-speaking women of Indian descent and combines rituals, prayer, songs, music, and dance. Nowadays, taking into consideration the contribution Geet-Gawai can make to breaking class and caste barriers, and the need to nurture social bonds in a multi-ethnic society, communities have expanded the practice to public performances so that neighbors can join in, and male performers are encouraged to participate in a spirit of social cohesion.3

With regard to knowledge concerning nature and the universe, knowledge holders continuously expand their knowledge systems in interaction with their environment and changing contexts. The Andean Cosmovision of the Kallawaya, for example, testifies to Kallawaya healers’ creation of a body of knowledge about medicinal plants, which they expand upon by travelling through widely varying ecosystems.4

In the domain of traditional handicrafts, communities demonstrate their capacity to innovate by diversifying production and distribution or finding new spaces for transmission, while maintaining the symbolic meaning of the creative process. In Pekalongan, a port city along the northern coast of central Java, Indonesia, batik-making skills are customarily passed down from generation to generation. This occurs by oral transmission and hands-on experience, often within the household. However, as young people spend most of their time at school, classroom instruction is now combined with age-appropriate hands-on activities. Handicrafts, including hand-drawn and hand-stamped batik, impact several facets of the creative sector of the city nowadays and hence greatly contribute to its economic development while ensuring the transmission of skills considered as important by local craft communities.5

Similarly, communities in Côte d’Ivoire engaged in a project to promote the creation of a balafon cultural industry by strengthening professional skills linked to this popular musical instrument. For the Senufo communities of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Côte d’Ivoire, cultural practices linked to balafon playing are part of their intangible cultural heritage. The practice provides entertainment during festivities, accompanies prayers, stimulates enthusiasm for work, and supports the teaching of value systems, traditions, beliefs, customary law, and the rules of ethics governing society and the individual in day-to-day activities.6

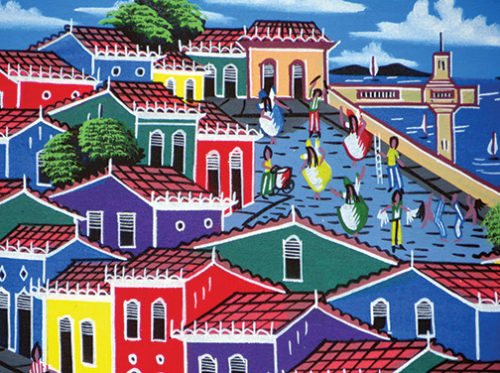

Vibrant colors depicting Bahia architecture and dancers celebrating during the carnival

The Bahia Carnival of Brazil is a striking example of how intangible cultural heritage provides the basis for a vibrant cultural activity that boosts the cultural industry in a major way. This carnival, which has an audience of around 900,000 people over six days, featuring more than 200 groups and involving around 12,000 artists, creates employment and attracts tourism. The commercialization of the carnival has nevertheless called for a regulatory response facing a twofold challenge: to safeguard the symbolic and cultural meaning of the festival for the identity of the bearers and communities involved while at the same time capitalizing on its revenue-generating potential.7

UNESCO recognizes that the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage is a powerful tool to promote community well being and mobilize innovative and creative responses to the challenges of sustainable development. In this regard, the General Assembly of States Parties to the Convention recently adopted an entire chapter for the Convention’s Operational Directives, ‘Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Development at the National.’ The chapter covers a wide range of development areas, including social, environmental, and economic aspects as well as peace building, which is core to UNESCO’s work.

There are numerous examples of the creative power that communities, groups, and in some cases individuals possess in addressing development challenges and fostering individual and collective well-being in light of past experiences and future aspirations. In the field of education, for example, communities have constantly found ways to create, systematize, and transmit their knowledge, life skills, and competencies to future generations, especially in relation to their natural and social environment. Much of this knowledge and many traditional methods of transmission are in active use today and could be incorporated into formal and non-formal education to stimulate learners’ creativity. Similarly, social practices of dialogue, conflict resolution, and reconciliation have a determining role to play in societies around the globe. They have been created over the centuries to respond to specific social and environmental contexts, help regulate access to shared spaces and natural resources, and enable people to live peacefully together.

A range of examples that demonstrate the mutually beneficial relationship between intangible cultural heritage and the above-mentioned development areas can be found in a UNESCO brochure entitled Intangible Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Development (http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002434/243402e.pdf). They illustrate the creative power of communities and groups worldwide who, by safeguarding their intangible cultural heritage, shape our common future and, as set out in the Preamble of the Convention, enrich cultural diversity and human creativity.

Notes

| 1. | ↑ | Objective 7 in UNESCO’s Medium-Term Strategy (2017 to 2021) says heritage is the assets that we wish to transmit to future generations because of the social value and the way in which these assets embody identity and belonging and help to promote social stability, peace building, crisis recovery, and development strategies. |

| 2. | ↑ | Al-Zaja, Recited or Sung Poetry was inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2014 (9.COM) |

| 3. | ↑ | Bhojpuri Folk Songs in Mauritius, Geet-Gawai was inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2016 (11.COM). |

| 4. | ↑ | Andean Cosmovision of the Kallawaya, originally proclaimed in 2003, was inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2008 (3.COM) |

| 5. | ↑ | For more information see “Education and Training in Indonesian Batik. Intangible Cultural heritage in Pekalongan, Indonesia.” (http://www.unesco.org/culture/ich/doc/src/24771-EN.pdf). |

| 6. | ↑ | Cultural practices and expressions linked to the balafon of the Senufo communities of Mali, Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire were inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2012 (7.COM). |

| 7. | ↑ | Creative Economy Report 2010: Creative Economy—A Feasible Development Option, UNCTD and UNDP |